Completing Sydenham on the Bruce Trail

Change in routine, Change in approach on the BTC

Waking up

and moving this morning, we endured physical challenges the like of which we

have never yet experienced. Our backs

hurt, our legs felt like rubber, and the bottoms of our feet were so sore that

instead of looking like intrepid hikers, we hobbled around our campsite like

aged crones. Nothing felt any better

over the hour it took us to make breakfast, enjoy our repast, and pack our gear

into our backpacks. I think each of us

wished that we could afford an extra day to spend more time at the Bass Lake

campground. Despite having to move on,

we were nonetheless very grateful for having had the opportunity to shower,

clean up, and dry off at the campground last night.

For the

past two days, being full of excitement for setting out on our hike, and

concerned that we would not get to our destination, we had pushed hard. This approach was clearly a mistake – and

last night we had to acknowledge that we can still reach our destination, even

if it takes a little longer each day. To that end, we have changed our approach

to this hike. As such, today we have decided

that we need to take more breaks to rest our bodies – perhaps stopping every

hour or two to rest and take off our shoes.

Sliding

our backpacks onto our sore shoulders, we gingerly retraced our route down

Sutherland Rd to the Bruce Trail. Here we rejoined the main pathway with only a

short section of the forested Lindenwood Management Area left. With our

bodies feeling a little better now that they had warmed up and were moving, we

navigated the muddy sections of the trail as we made our way northward.

Around

thirty minutes later we emerged from the dense forested area into an open field. From there we followed a fence line for a

bit, before beginning a 4-5 kilometre stretch of easy roadway and access road

walking, tracing the gravel routes of Cole’s Sideroad. En route, small marshy sections lined the

roadway and bird boxes dotted the top of farm fence posts. We trekked the length of pastures filled with

cows that were a mixture of curious and cautious as we ventured past.

Possibilities and Side Trails

We

reached the intersection of the roadway and the entrance to the Kemble Mountain

section of the Bruce Trail after an hour of hiking. There we decided to take a break in the midst of a lovely apple orchard. Sitting down

with our backpacks off and Clif Bars in our hands, we pulled out Map 34 from

the Bruce Trail Guidebook.

Almost

instantly all three of us noticed the same thing – that the main trail toured

some 10 kilometres around Kemble Mountain Management Area, only to return a few

hundred feet away from our present position.

After this, the BTC ventured 5 kilometres up the long and rocky Colpoy’s

Range Rd. By contrast, a side trail

which traversed the Slough of Despond was a “mere” 8 kilometres in length. Our choice was hiking 16 kilometres versus 8

kilometres to get to the same point.

Hmmm…..

Here I

will admit that there is nothing more tempting in life than a shortcut made available

to you when you are sore and uncertain.

The prospect of not weaving around Kemble Mountain and then climbing up

a long stretch of roadway stood out, especially when there was an official

Bruce Trail route that would make today both shorter and a little easier. This shortcut would also make the

possibility of getting to the city of Wiarton much more likely. Wiarton meant a hotel room, a large dinner,

and comfort! We estimated we could reach

Wiarton in about 6 hours if we took the side trail. By contrast, the main route would take 8-9

hours.

Needless

to say, it did not take much discussion, especially given the challenges of the

first two days, to be convinced that following a side trail through the Slough of

Despond would make the day easier.

Especially since, beyond hiking from Owen Sound to Tobermory, the goal

of this summer’s venture is to inspire a love of nature in a younger family

member. If every day’s trek was an

unending march from dawn to dusk, it was highly likely that the outdoors would

not endear itself to this young man.

Seeing him sitting on the ground, we knew that we had to change gears and change our approach, lest he end up hating nature because we pushed too

far too fast.

With that

said, nothing raises the spirits more than an announcement that the day’s hike

will be shorter, and easier, and that it will end with ice cream and a motel bed!

Slough of Despond

Heaving

our backpacks back on, we trekked eastward down the Slough of Despond Side

Trail away from the main BTC pathway.

Following the rarely used concession road amid waist-high reeds, we soon

turned onto an access route which took us directly to the escarpment

overlooking the marshlands of the region.

There we began to weave between ponds of sitting water and bogs filled

with songbirds, reeds, and biting mosquitoes.

Having worked in the backwoods of Canada for a number of years, I have

garnered a healthy respect for places with unique names. I have long since given up on the belief that

such locations have been so named out of any sense of history or imagination,

and instead come to terms with the fact that many places have names which are

descriptive of local realities.

The truth

is, however, the name of this region refers to a location in John Bunyan’s text

“The Pilgrim's Progress”. For Bunyan, the

Slough of Despond is a place of challenge through which all must cross and be

tested in order to get to their final destination. Marching with bug nets over our heads, and

our limbs liberally sprayed with Ben’s insect repellant, the idea that we were being

tested certainly seemed to fit our present circumstances. Our resident teenager also began to

repeatedly mutter the word “despond”, “despond”, “despond” – a clear warning of

his changing mood about this region.

About all I can say is that at least the mosquitoes were grateful for us

to be venturing through there – though I had admittedly begun to wonder if we

were being punished for not sticking to the main route of the Bruce Trail. Was this hiker karma for us shortening the

route? Regardless of our doubts or

circumstances, there was to be no turning back, the decision had been made, and

we were on our way.

A thing or two about Wetlands…

Sometime

during this stretch of mosquitoes and black flies, our younger family member

asked a great question – what is the difference between a marsh and a slough? While we did not have the answer on hand, the

question would lead us to look it up later.

As it turns out, the answer is a little more complex than merely

distinguishing between these two terms. According to the BTC guidebook, the

Slough of Despond is an Area of Natural and Scientific Interest, which means

that it is a region that contains features that represent lands and waters that

are important for natural heritage, protection, appreciation, and scientific

study.

The

region of the Slough of Despond is a wetland that was formed by a barrier beach

created by Lake Algonquin, which is the glacial precursor of Georgian Bay. Unlike many other marshy regions across

Ontario and Canada, it has not been drained.

Wetlands, despite being essential habitats for bird life and amphibians,

as well as their amazing ability to clean drinking water, have long been

coveted for the nutrient-rich soil they produce, which makes perfect

farmland.

These

details aside, back to the original question – What is the difference between a

marsh and a slough? Well, in a general

sense, they are both wetlands, as are swamps, blogs, fens, morass, and

everglades. Each of these geographical

features is characterized and distinguished from one another by the plant life

they hold, where their water source originates, how much water they hold, and

whether they give way to the decomposition of organic material or not. Accordingly…

Wetlands are low-lying regions saturated with water,

either seasonally or permanently. The term wetland is also used more broadly to

refer to swamps, marshes, and bogs, which are similar but have a number of key

differences.

Specifically,

swamps are forested wetlands that

are located near where the land meets with a large lake or river. Swamps tend to be along waterways, located

either amid flood plains or in coastal, intertidal, regions and they are often

defined by the type of tree growing in them.

Swamps in particular tend to have slow-moving water that supports woody

plants, such as cypress trees and shrubs, and they can be in either fresh or

saltwater regions.

Alternatively,

marshes are similar to swamps but

have few trees and are instead filled with softer non-woody plants like

grasses, cattails, or reeds. Marshes can

also be either fresh or saltwater but produce rich waterlogged soil that supports

plant life. In general, there are three

types of marshes: tidal freshwater, tidal saltwater, and inland freshwater.

Yet

another area is a bog, which is

often confused with both swamps and marshes.

Fed primarily by rainwater, bogs are actually highly acidic and have

low oxygen levels. As a result, organic

matter accumulates faster than it decays, and so bogs are characterized by an

accumulation of peat and leftover dead plant material. In addition, this lack of nutrients means

that bogs have an inability to support plant life. Bogs achieved notoriety as a source of peat

moss, which has historically been harvested for burning, as a source of fire

and heat.

The final

distinction is a slough, which is

actually a mixture of swamps and marshes.

Sloughs are typically the result of backwater from a river and have a

large amount of dead plant material, such as decaying leaves that have formed

topsoil.

Beyond

these ecological features, there are still more distinctions such as fens,

(groundwater bog), mires, morass (impassible swamp or bog), and

everglades. Each of these has its own

characteristics and unique role amid large regional ecosystems.

With our

bug nets tightly on and our heads down, we pushed through the dense forest

filled with ferns, fungus, and flowers, which overlooked the main wetland

below. Beyond the swarms of mosquitoes,

my memory of this section is of an easy stretch of trail that was somewhat

overgrown, but which was still identifiable and passable. At a number of points, we were provided with

beautiful lookouts over the region before following the President’s Path to the

northern boundary of the Slough.

Reaching Colpoy’s Range Rd, we climbed and descended the stile over the

rough wood rail fencing, and rejoined the main Bruce Trail, which had been

running along roadways for almost 10 kilometres prior to beginning its climb to

reach Skinner’s Bluff.

A Break and a Decision

By the

time of our arrival on Skinner’s Bluff, we had reached our “soft goal” or

fallback destination for the day. More

exciting for us was that it was still before noon – this marked the first time

with a younger relative on our trek that we had covered our goal for the day. There, on the side of the roadway, we took

our second break for the day. I must

admit that the Bass Lake campground hosts had told us this morning that if we

wanted to get picked up at this location and brought back to Bass Lake for

another night, we should give them a call.

It was such a gracious offer, and one that I admit seriously tempted

me. As we enjoyed a few snacks and

water while taking in views of Colpoy’s Bay, we again talked about what to

do. To our surprise, it was the teenager

of the group who was most adamant that the remaining 16-18 kilometres to

Wiarton “could easily be handled this afternoon.” The switch had been thrown from grumbling and

stumbling, towards pushing on.

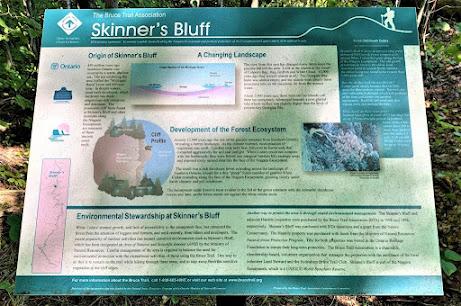

Skinner’s Bluff Management Area

With

cooler weather and beautiful views, we soon headed off, with Wiarton as our

goal. Skinner’s Bluff Management Area is clearly a popular area, a fact which

soon became clear from the sheer number of cars parked everywhere along the

roadway at the entrance. Passing blue

signs for Skinner’s Bluff, we stepped onto the narrow, hard-packed path that

traced the top ridge of the escarpment for the next 8 kilometres. Trekking on, the landscape slowly climbed to

the pinnacle of the bluff, which overlooked Colpoy’s Bay. En route, we navigated a constant maze of

tree roots sprawling across the trail, and the (now usual) rocky terrain amid a

dense forest, which provided welcome shade amid the afternoon’s rising

temperatures.

As we

covered the kilometres we passed a number of staggering and unnerving drop-offs,

which doubled as lookouts for the intrepid masses taking pictures at them. Unfortunately, we didn’t really get a great

view of the bay, as much of the view was obscured by the haze and humidity of

the day, and most of the lookouts were filled with crowds of people. With little interest in waiting for a

fleeting look, we simply continued on.

Heading west, the dirt pathway widened out as it slowly navigated around

the bay toward Wiarton. Interestingly,

Colpoy’s Bay and other similarly named sites in this region are named after the

eighteenth-century British Naval Vice-Admiral Sir Edward Griffith Colpoys. This

distinguished gentleman engaged a naval fleet at the Battle of Cape Finisterre

during the Napoleonic War (a location known by many on the Camino de Santiago),

participated in the War of 1812 by re-establishing British control of Maine,

and later served as the commander of the navy in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

After

almost 2 hours and 7 kilometres of hiking the Skinner’s Bluff section, the

trail seamlessly took us into the Bruce’s Caves Conservation Area.

Bruce’s Caves Conservation Area

Following

the wide, flat pathway, we soon arrived at the BTC side Trail to Bruce’s Caves

– which we took the opportunity to explore and rest. Venturing down the side of the escarpment

amid the trees and mosses, we soon arrived at the geological feature known as

Bruce’s Caves. Interestingly, they were

named after a hermit, Robert Bruce, who owned and lived on the property in the

early part of the twentieth century, and subsequently began to charge people to

visit the caves. After he passed away

in 1908, there were no longer any fees for visiting this region and exploring its

unique rock formations. The largest of

the caves is a huge cavern and is distinctive for the double arch at its

entrance.

According to our Bruce Trail

Guidebook, this cavern was likely formed by the wave action of Lake Algonquin as it

washed against the soft limestone of the Niagara Escarpment. Walking into the wave, we marvelled at its

sheer size, as well as the knowledge that much of this was at one point

underwater.

While all

this natural beauty might seem to be the key attraction - for a group of hikers,

it was in fact the picnic tables and washrooms which stood out the most upon

our arrival. There is no denying that by

the time we had reached Bruce’s Caves, we were tired, footsore, and questioning

our earlier decision to push as far as Wiarton.

Having now covered almost 30 kilometres of trail today, and still having

about 7 kilometres more to go, we welcomed the opportunity to sit down and rest

without our backpacks on.

Isn’t it

odd how the notion of walking 7 kilometres seems like nothing, but the

realities of trekking 7 kilometres more after already covering 30 kilometres,

can be so mentally exhausting?

Road Walking and Road Allowances

Shortly

after setting back onto the main route of the Bruce Trail, the path left the

forest and escarpment ridge behind and followed Grey Road 1 heading into

Wiarton. Approaching the end of a long day

(our longest at this point) on the Bruce Trail, we welcomed the easy road

walking into town. With little more than

determination driving us, we trekked past weathered barns and open agricultural

fields. We passed through the community

of Oxenden, and now only a few kilometres out of Wiarton, had to contend with

the increase in local traffic. Despite

how busy this stretch was, we nonetheless enjoyed having a break from the

cracks and crevices which had dotted the landscape and pathway since before

Owen Sound.

After 30

minutes of walking along roadways, the BTC wove onto the property of the

Wiarton Airport, otherwise known as Wiarton Keppel International Airport. Entering into this stretch, we departed the

road and began venturing along a wide muddy track amid waste-high grass. Here our shoes and socks were soon soaked

through as we trekked past wide open fields and the long paved runways. Above us, small aircraft took off and flew

overhead, while frogs squeaked as they hurriedly vacated the puddles around

us.

Wiarton and Groundhog’s Day

The trail

eventually led us down off the bluffs on a step ladder, and we emerged onto the

city streets of Wiarton! We had covered

38 kilometres, and we had made it! Walking through town, we passed signs for

downtown, the campground, and the extensive Great Lakes Waterfront Trail. The

Waterfront Trail is a signed, 3,600-kilometer-long route connecting 155

communities across Ontario, which gives users the possibility of following

along the shorelines of the Great Lakes.

We had already seen signs for the Great Lakes Waterfront Trail in

Niagara, Hamilton, and Toronto, but were somewhat surprised to see it again

here.

The city

of Wiarton is located at the southern end of Colpoy’s Bay, and it was established

in the 1850-1860s along an Indigenous portage route, and as the headquarters

for the regional logging industry. The

town was named Wiarton in 1868 after the birthplace of Sir Edmund Walker Head,

in Kent England, who was the governor of the province of Canada (1854-1861) at

the time the region was surveyed. By the

late nineteenth century, Wiarton also became central to the province’s fishing

industry, and it was connected to other urban centers through the Grand Truck

Railway. Unfortunately, during the 1940s, the decline in timber supplies, fish

catches, and the increased reliance on roads throughout the country led to the

collapse of Wiarton’s key industries.

Since then, it has transitioned to being a tourist destination, which is

known across North America since 1956 for its annual celebration of Groundhog’s

Day.

|

| Wiarton, 2004 |

Walking

into Bluewater Park on the city’s waterfront, we arrived at a 4.5-ton groundhog

statue known as “Willie Emerges”. This

commemorative icon is carved from dolomite stone from the Niagara

Escarpment. On previous visits, we have

come here to see both the living Wiarton Willie in his enclosure and this

statue. Today, however, thoroughly

exhausted, we arrived at the water’s edge and simply walked on without

pause. Soon after, we arrived at the

municipal campground and shaded picnic area, where we stopped to rest, get our

bearings, and reserve a motel room for the night.

Sydenham Section / Peninsula Boundary

The

history of Wiarton, and the presence of Wiarton Willie aside, our arrival in

town meant that we had reached the “Gateway to the Bruce Peninsula.” And while today we are simply grateful to

have gotten 68 kilometres of the Bruce Trail from Owen Sound to Wiarton

completed – in a wider sense of things, getting here means that we have

officially passed out of the Sydenham Section of the BTC and are now at the

beginning of the Peninsula Section!

It

also means, in terms of our other hikes and adventures on the BTC, that we have

hiked approximately 732 kilometres, have a “mere” 165 kilometres to go before

Tobermory and our goal of walking the entire Bruce Trail from south to north is

achieved!

Rest, Resupply, and Reflection

Getting

to Wiarton this evening means that we are due for a large celebratory dinner, a

warm shower, and a night in a local motel.

Today’s trek between Bass Lake and Wiarton took us over a diversity of

landscapes across fields, down country lands, through forests, along the ridge

of the Niagara Escarpment, and into ancient caves. While the distance was physically challenging,

the Bruce Trail itself made for relatively easy going through the Slough of

Despond and along Skinner’s Bluff.

We have

now trekked 72 kilometres over 3 days on the BTC, with an estimated 164

kilometres left to cover before Tobermory. Regardless of what lies ahead, we

are definitely feeling better with today’s accomplishment – driven by the energy

and excitement of the youngest member of the group!

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.JPG)

Comments

Post a Comment